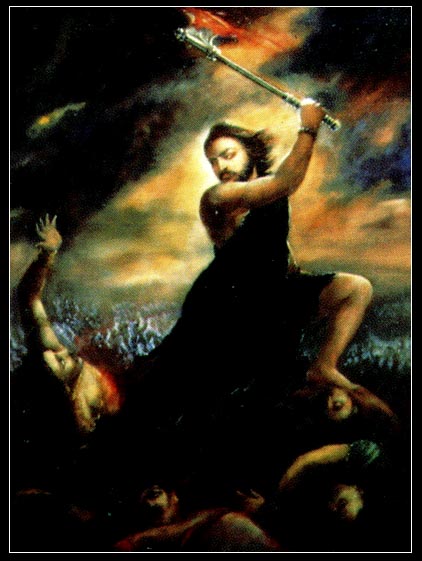

Of all the avatars of Vishnu, none is stranger than that of Rama-with-the-axe. His real name was Jamadagnya, but this favored weapon was the battle-axe or Parashu, and it was combined with his pet name Rama, to give him the appellation by which we know him. As to why he was called Rama, when his name was Jamadagnya, there is no indication. It is merely one of the typical incongruities surrounding his entire life.

To begin with, this sixth avatar of Vishnu was a brahmin and should never have been a warrior, let alone the epitome of battle fury that he became. His wild and passionate nature is matched in all epic literature only by Cuchullihain of the Irish myths. Officially his mission - all avatars have a mission - is to clear the earth of the Kshatriya or warrior caste, which was making a nuisance of itself on Earth. This is a very feeble attempt to disguise plain and simple prejudice on his part as a divine plan. For the man was totally immune to reason. It was not enough that he killed off the Kshatriyas who murdered his father. He went after the entire community and wiped them out. Then he wiped out the sons who had survived and he did this for twenty-one generations. This is usually behavior of asuras, rakshahsas and danavas, not of divine personages. It was beyond all justice, all norms of sanity even. It is also perhaps the reason why there are hardly any temples in his name. He was never a popular avatar, not now, and not in the past.

He seemed to have a massive chip on his shoulder and a pugnacious attitude that was capable of instantly flaring up into an annihilating battle fury. My own take on his peculiar psyche is that he was an oddball and had the misfortune to have it pointed out to him early and regularly. For his birth was the result of an accident. His grandmother, Satyavati, mixed up a magic potion, that she and her sonless mother were to take, so that they could have the eternally desired for sons. As a result the warrior prince became a brahmin monk in attitude and she was going to have a killer and warrior for a son. Her husband was a sage however, and he modified the consequences of the mix-up long enough so that it would be the grandson and not the son who would be the warrior. That grandson was Parashurama.

It is obvious that his parents would be keeping a wary eye out on each of their offspring - anxiously waiting for the signs that would proclaim the misfit, the lover of weapons instead of holy texts. The first four sons they had were normal and studious brahmin boys. His father Jamadagni, another irascible temperament, and his mother Renuka, may have relaxed a bit prematurely. For the fifth was definitely the dreaded warrior. It is impossible to convey the sheer moral horror brahmin parents would endure when their son turned out to be a warrior in temperament, though there was nothing wrong with his ability to learn. To kill and fight is unthinkable for them and here was this young hellion who loved nothing else. It was also a breaking of the boundaries of the caste-profession another peculiar horror for the Indian mind. He was supposed to pore over texts, not work out with weapons. There is no doubt that the young boy was far from being the favorite of his parents, though he seems to have thereby developed a fierce need to win his father's approval at any cost. One can only guess at the deep unhappiness of a boy, conscious that he has within him a vast - not a talent or aptitude - but a positive genius for war but that is not what is the approved skill of his family. Add to this the fact that he was the bottom of the pecking order, with four older brothers, and we can understand where he got this relentless anger from.

He went off to the Himalayas to practice austerities and win the favor of the great god Shiva. This he did easily, as his formidable will power made him a natural for tapasya. When the god appeared however, his innate genius would not be denied and he asked for supreme mastery over all weapons as his boon rather than any desire for wealth or learning. His favorite weapon was the battle-axe and Shiva taught him how to use it so that he was invincible. He also became the greatest archer of his day.

On his return to his father's ashram, he found out that stirring times had come to the placid life of the hermitage. His mother had sinned in the eyes of his father who had pretty austere standards and he was vainly exhorting his older sons to kill her! Renuka was a pativrata, a woman inviolable in her chastity and faithfulness to her husband and a possessor of magical powers as a consequence. She did not even need a pot to bring water from the river, she just used to shape the flowing water into a pot form and carry it home. That unfortunate day however, she had seen the prince of Mrittikavati, Chitraratha, making whoopee with his wives in the river. This was a very typical ancient practice to lend some variety to the pleasures of the conjugal bed. The sight made her feel a bit envious as well as sorry for herself that such pleasures were not for her. Instantly her power of chastity deserted her and she could no longer form the water into a pot. Jamadagni, being a sage knew what had happened and he was in one of his typical rages when Parashurama returned.

The other sons felt that the old man was overreacting and anyway, there was no way they were ever going to harm their mother let alone kill her. Not so Parashurama, who swung his axe once, and had a decapitated mother. This act of Parashurama has never been seriously examined by Hindu commentators. At best they put up a piffling defense that he was being obedient to his father, and obedience was an obsession with the old Hindus, perpetually afraid that children would turn out to be impertinent. That it is so obviously an outburst of temper aimed at getting a bit of his own back, a retaliation for the feeling of neglect and being viewed with suspicion, if not active dislike, is so obvious that nobody ever says it out loud. There is just this peculiar reluctance to look at Parashurama, his myths are hurriedly given a cursory once over and then you move with relief to the safer territory of Rama and Krishna. For dangerous truths about the nature of interfamily relationships would come out if you explored the story of Parashurama too closely, it is a disturbing denial of the comforting myth of the perfect and cozy comfort zone the family is desperately hoped to be. This is Hindu India's greatest contribution to the psychological truth of hatred within families and of course it is completely at a subconscious level.

When Parashurama acted so promptly, Jamadagni was shocked back into his senses. By the norms of the time, the blame for this action would be all his, a father's command is paramount. His father asked him to receive a boon for this murderous promptitude. The canny young man chose eternal life, invincibility in battle (which he already had because of Shiva) and that his mother would be restored to life in her original purity. A head however was needed. This amazing person, according to a very popular myth in Andhra Pradesh, stalked down to the river and cut off the head of the first woman he saw. This happened to be a shudra, the lowest of low castes, which shows that his animosity to his mother was not quite over. Even the shadow of a shudra was regarded as polluting and to have to bear the head of one,. there is a touch of a refined and inspired sense of malice in this choice. However he was now the favorite, he had to be. His mother had been brought back to life and restored to the good graces of her husband and that is the only thing that really mattered for women at that time. Parashurama's triumph was even more complete because his hasty father had just cursed his brothers to become imbeciles.

Thus ended the first important passage of the life of Parashurama. He had finally gained his parents' approval, when a disaster struck the happy family. The King of the Haiyahayas, Kartivirarjuna, coveted a sacrificial calf belonging to Jamadagni. When the sage expressed his disinclination to part with it, he just carried the calf away. He thought he had to deal with the usual intellectual Brahman, but this was the action that called his death to him. Kartivirarjuna was a thousand armed king who had once humbled the great Ravana, but had now become somewhat of a demon himself. Parashurama assaulted his palace, massacred everybody within, and cut off all the arms of the king before sweeping off his head.

As to whether this was not overkill, for the sake of a calf, he had no time for such subtleties. He was appallingly direct and devastatingly simple in his solutions to all problems, an early version of the queen of hearts in the Alice Stories. Everything was "Off with his head". So limited was his comprehension and so sure was he that he had right and justice on his side, that he never seems to have consciously contemplated retaliation on the part of the king's sons. He actually left his father alone while he went to cut firewood and obviously the king's sons slaughtered the poor old sage. This absence of the axe man is curious and very significant. Perhaps he got the approval he wanted, but subconsciously he still had some resentment against his father. Nothing else will explain this breathtaking confidence at leaving the old man alone and unprotected. It was an act of immense stupidity, the consequences of which could have been foretold by any fool, and Parashurama was no fool.

He launched his famous Kshatriya-cleansing campaign, an action that is so gratuitously violent that it could only be indicative of deep seated and eternally smoldering caste animosity, which a too-imaginative brahmin writer inserted into his life-story as some sort of vicarious revenge against a despised caste. He filled up seven lakes with the blood of his foes, as always he had no sense of limits. Then he repented!

He gave back the kingdoms to the princes and retired to do penance for his actions. He was told that he would have to make land grants to brahmins as part of this purification, but there was not a piece of earth that he had not soaked with blood. His greatest feat came next, in an attempt to provide land that was untainted. He reclaimed land from the ocean, to the extent that was covered by the hurling of his Parashu. That is the modern state of Kerala in India and its Sanskrit name is still Parushurama-shetra, the land of Parashurama. Geologically, too there is some truth to this myth, Kerela being one of the last land areas in India to surface from the ocean.

Even though the axe-bearer is acknowledged as the creator of Kerala, there is only one or at best two temples to him in his own country! Parashurama is like the Vedas, nominally respected and actually neglected. Once he had gifted away the new land, and expiated himself of his sins, he wanted to gift the brahmans settled there his supreme gift - knowledge of the martial arts. They were properly horrified whereupon he angrily sought out their children born out of marriages with non-brahman women, (the present day Nair community) and he taught them the world's oldest martial art, Kalaripayyattu. As is inevitable by now, not a single Kalari school in Kerala has him as the presiding deity, they are all goddess shrines, though he is given the credit for introducing the art, if not inventing it. There is a curious double-process of acknowledgement and respect along with denial and rejection that always dogs Parashurama.

Parashurama had unique powers of locomotion and could cover many hundreds of miles in a few minutes, always preceded by dust-clouds and storm winds. As a metaphor for his personality, nothing could be more apt. His being immortal led to many curious adventures in times that were not really his own. He was an aspect of godhead that had outlived its own natural span and created trouble in changed times. He met the next avatar of Vishnu, Rama, and acknowledged him as his superior in a trail of strength that involved stringing Vishnu's bow. Scholars are of the opinion that this story was interpolated into the Ramayana, when Rama was changing from a great hero to an aspect of god in the popular mind. If the great Parashurama acknowledged him as god then the metamorphosis was complete. Parashurama was obviously once a popular god, but the forces of social conservationism were never quite at ease until more acceptable aspects of divinity subsumed this chaotic element.

He appears in the Mahabharahta too and seems to have set aside his eternal disdain for Kshatriyas for a while. For he trains Gangeya, the later Bhisma, and makes him an invincible warrior. This he learns to his own cost, because he goes up against his former pupil and has the mortification of not being able to best him, and even being in some danger of defeat before the gods intervene and stop this planet threatening combat. (He has a similar tiff with Ganesha too, and is credited with knocking off one of the tusks of that god, but the issue remained inconclusive in that instance also). His fighting Bhisma was actually something pretty remarkable, for he was fighting on behalf of a Kshatriya princess who felt she had some claim to becoming Bhisma's wife. Bhisma was like Parashurama, a lifelong celibate, and he flatly refused to imitate his guru's obedience. The important part of this story is that Parashurama could actually unbend enough to become a mentor to a hated Kshatriya and champion the cause of a girl from the same caste. The many long years he had lived had obviously softened him somewhat.

This defeat at the hands of Bhishma seems to have soured him once more, for he again refused to teach anybody but brahmins. Karna, one of the great heroes of the Mahabharatha, was of too low a Kshatriya caste to be taken notice of by Kshatriya martial arts masters. So he lied to the axe-man that he was an unfortunate brahman boy cursed with a talent for fighting and unable to get anybody to take him seriously. This lie must have gone to the soul of Parashurama, for he had been there. He immediately set about making the boy into a great warrior. Unfortunately for him, Karna had too much of his caste fortitude. Once, while his irascible guru was sleeping with his head on the boy's lap, a flesh-eating ant attacked Karna's thigh. His hands were not free as they were cradling the guru's head and rather than disturb the guru, he bore the pain. On waking up and seeing the blood, his guru instantly understood that the boy was a true Kshatriya, for only they could bear pain on behalf of others. Instead of admiring the boy for this fortitude and self-sacrifice, the angry avatar cursed him that he would lose his knowledge at the supreme crisis of his life and fall ignominiously in battle as a consequence. This was the authentic Parashurama note being sounded once again, relentless, furious and implacable in anger.

It has been theorized that the axe-man was perhaps a forest god who was gradually absorbed into Hinduism and given the status of an avatar of Vishnu. I doubt it. Forest gods are never so ferocious and perpetually in a bad mood. This is the Raudra Rasa incarnate, pure anger, the wrath of god in no uncertain terms. It has also been theorized that the story is an unconscious understanding of the process of evolution. The dwarfish human is succeeded by the brutal and hasty type before it is superceded by the more refined and elegant modern man. That is reasoning backwards and forcibly applying a theory to explain away what is uncomfortable to modern sensibilities. In any case, traditional Hindu theories of evolution speak of the devolution of man and his ages, not of his evolution, so Parashurama should be a modern, not an ancient type of god.

Whatever be the reasons, real and imagined, behind this fascinating aspect of the concept to avatars, there is no doubt that Parashurama is a real puzzle. It is perhaps in recognition of this perplexity that the ancient commentators called him both Khanda-parashu, he-who-strikes-with-an-axe as well as Nyaksha - the inferior (avatar). This incarnation is definitely a bit too strong for the average stomach and hence the respectful neglect he is held in.

To begin with, this sixth avatar of Vishnu was a brahmin and should never have been a warrior, let alone the epitome of battle fury that he became. His wild and passionate nature is matched in all epic literature only by Cuchullihain of the Irish myths. Officially his mission - all avatars have a mission - is to clear the earth of the Kshatriya or warrior caste, which was making a nuisance of itself on Earth. This is a very feeble attempt to disguise plain and simple prejudice on his part as a divine plan. For the man was totally immune to reason. It was not enough that he killed off the Kshatriyas who murdered his father. He went after the entire community and wiped them out. Then he wiped out the sons who had survived and he did this for twenty-one generations. This is usually behavior of asuras, rakshahsas and danavas, not of divine personages. It was beyond all justice, all norms of sanity even. It is also perhaps the reason why there are hardly any temples in his name. He was never a popular avatar, not now, and not in the past.

He seemed to have a massive chip on his shoulder and a pugnacious attitude that was capable of instantly flaring up into an annihilating battle fury. My own take on his peculiar psyche is that he was an oddball and had the misfortune to have it pointed out to him early and regularly. For his birth was the result of an accident. His grandmother, Satyavati, mixed up a magic potion, that she and her sonless mother were to take, so that they could have the eternally desired for sons. As a result the warrior prince became a brahmin monk in attitude and she was going to have a killer and warrior for a son. Her husband was a sage however, and he modified the consequences of the mix-up long enough so that it would be the grandson and not the son who would be the warrior. That grandson was Parashurama.

It is obvious that his parents would be keeping a wary eye out on each of their offspring - anxiously waiting for the signs that would proclaim the misfit, the lover of weapons instead of holy texts. The first four sons they had were normal and studious brahmin boys. His father Jamadagni, another irascible temperament, and his mother Renuka, may have relaxed a bit prematurely. For the fifth was definitely the dreaded warrior. It is impossible to convey the sheer moral horror brahmin parents would endure when their son turned out to be a warrior in temperament, though there was nothing wrong with his ability to learn. To kill and fight is unthinkable for them and here was this young hellion who loved nothing else. It was also a breaking of the boundaries of the caste-profession another peculiar horror for the Indian mind. He was supposed to pore over texts, not work out with weapons. There is no doubt that the young boy was far from being the favorite of his parents, though he seems to have thereby developed a fierce need to win his father's approval at any cost. One can only guess at the deep unhappiness of a boy, conscious that he has within him a vast - not a talent or aptitude - but a positive genius for war but that is not what is the approved skill of his family. Add to this the fact that he was the bottom of the pecking order, with four older brothers, and we can understand where he got this relentless anger from.

He went off to the Himalayas to practice austerities and win the favor of the great god Shiva. This he did easily, as his formidable will power made him a natural for tapasya. When the god appeared however, his innate genius would not be denied and he asked for supreme mastery over all weapons as his boon rather than any desire for wealth or learning. His favorite weapon was the battle-axe and Shiva taught him how to use it so that he was invincible. He also became the greatest archer of his day.

On his return to his father's ashram, he found out that stirring times had come to the placid life of the hermitage. His mother had sinned in the eyes of his father who had pretty austere standards and he was vainly exhorting his older sons to kill her! Renuka was a pativrata, a woman inviolable in her chastity and faithfulness to her husband and a possessor of magical powers as a consequence. She did not even need a pot to bring water from the river, she just used to shape the flowing water into a pot form and carry it home. That unfortunate day however, she had seen the prince of Mrittikavati, Chitraratha, making whoopee with his wives in the river. This was a very typical ancient practice to lend some variety to the pleasures of the conjugal bed. The sight made her feel a bit envious as well as sorry for herself that such pleasures were not for her. Instantly her power of chastity deserted her and she could no longer form the water into a pot. Jamadagni, being a sage knew what had happened and he was in one of his typical rages when Parashurama returned.

The other sons felt that the old man was overreacting and anyway, there was no way they were ever going to harm their mother let alone kill her. Not so Parashurama, who swung his axe once, and had a decapitated mother. This act of Parashurama has never been seriously examined by Hindu commentators. At best they put up a piffling defense that he was being obedient to his father, and obedience was an obsession with the old Hindus, perpetually afraid that children would turn out to be impertinent. That it is so obviously an outburst of temper aimed at getting a bit of his own back, a retaliation for the feeling of neglect and being viewed with suspicion, if not active dislike, is so obvious that nobody ever says it out loud. There is just this peculiar reluctance to look at Parashurama, his myths are hurriedly given a cursory once over and then you move with relief to the safer territory of Rama and Krishna. For dangerous truths about the nature of interfamily relationships would come out if you explored the story of Parashurama too closely, it is a disturbing denial of the comforting myth of the perfect and cozy comfort zone the family is desperately hoped to be. This is Hindu India's greatest contribution to the psychological truth of hatred within families and of course it is completely at a subconscious level.

When Parashurama acted so promptly, Jamadagni was shocked back into his senses. By the norms of the time, the blame for this action would be all his, a father's command is paramount. His father asked him to receive a boon for this murderous promptitude. The canny young man chose eternal life, invincibility in battle (which he already had because of Shiva) and that his mother would be restored to life in her original purity. A head however was needed. This amazing person, according to a very popular myth in Andhra Pradesh, stalked down to the river and cut off the head of the first woman he saw. This happened to be a shudra, the lowest of low castes, which shows that his animosity to his mother was not quite over. Even the shadow of a shudra was regarded as polluting and to have to bear the head of one,. there is a touch of a refined and inspired sense of malice in this choice. However he was now the favorite, he had to be. His mother had been brought back to life and restored to the good graces of her husband and that is the only thing that really mattered for women at that time. Parashurama's triumph was even more complete because his hasty father had just cursed his brothers to become imbeciles.

Thus ended the first important passage of the life of Parashurama. He had finally gained his parents' approval, when a disaster struck the happy family. The King of the Haiyahayas, Kartivirarjuna, coveted a sacrificial calf belonging to Jamadagni. When the sage expressed his disinclination to part with it, he just carried the calf away. He thought he had to deal with the usual intellectual Brahman, but this was the action that called his death to him. Kartivirarjuna was a thousand armed king who had once humbled the great Ravana, but had now become somewhat of a demon himself. Parashurama assaulted his palace, massacred everybody within, and cut off all the arms of the king before sweeping off his head.

As to whether this was not overkill, for the sake of a calf, he had no time for such subtleties. He was appallingly direct and devastatingly simple in his solutions to all problems, an early version of the queen of hearts in the Alice Stories. Everything was "Off with his head". So limited was his comprehension and so sure was he that he had right and justice on his side, that he never seems to have consciously contemplated retaliation on the part of the king's sons. He actually left his father alone while he went to cut firewood and obviously the king's sons slaughtered the poor old sage. This absence of the axe man is curious and very significant. Perhaps he got the approval he wanted, but subconsciously he still had some resentment against his father. Nothing else will explain this breathtaking confidence at leaving the old man alone and unprotected. It was an act of immense stupidity, the consequences of which could have been foretold by any fool, and Parashurama was no fool.

He launched his famous Kshatriya-cleansing campaign, an action that is so gratuitously violent that it could only be indicative of deep seated and eternally smoldering caste animosity, which a too-imaginative brahmin writer inserted into his life-story as some sort of vicarious revenge against a despised caste. He filled up seven lakes with the blood of his foes, as always he had no sense of limits. Then he repented!

He gave back the kingdoms to the princes and retired to do penance for his actions. He was told that he would have to make land grants to brahmins as part of this purification, but there was not a piece of earth that he had not soaked with blood. His greatest feat came next, in an attempt to provide land that was untainted. He reclaimed land from the ocean, to the extent that was covered by the hurling of his Parashu. That is the modern state of Kerala in India and its Sanskrit name is still Parushurama-shetra, the land of Parashurama. Geologically, too there is some truth to this myth, Kerela being one of the last land areas in India to surface from the ocean.

Even though the axe-bearer is acknowledged as the creator of Kerala, there is only one or at best two temples to him in his own country! Parashurama is like the Vedas, nominally respected and actually neglected. Once he had gifted away the new land, and expiated himself of his sins, he wanted to gift the brahmans settled there his supreme gift - knowledge of the martial arts. They were properly horrified whereupon he angrily sought out their children born out of marriages with non-brahman women, (the present day Nair community) and he taught them the world's oldest martial art, Kalaripayyattu. As is inevitable by now, not a single Kalari school in Kerala has him as the presiding deity, they are all goddess shrines, though he is given the credit for introducing the art, if not inventing it. There is a curious double-process of acknowledgement and respect along with denial and rejection that always dogs Parashurama.

Parashurama had unique powers of locomotion and could cover many hundreds of miles in a few minutes, always preceded by dust-clouds and storm winds. As a metaphor for his personality, nothing could be more apt. His being immortal led to many curious adventures in times that were not really his own. He was an aspect of godhead that had outlived its own natural span and created trouble in changed times. He met the next avatar of Vishnu, Rama, and acknowledged him as his superior in a trail of strength that involved stringing Vishnu's bow. Scholars are of the opinion that this story was interpolated into the Ramayana, when Rama was changing from a great hero to an aspect of god in the popular mind. If the great Parashurama acknowledged him as god then the metamorphosis was complete. Parashurama was obviously once a popular god, but the forces of social conservationism were never quite at ease until more acceptable aspects of divinity subsumed this chaotic element.

He appears in the Mahabharahta too and seems to have set aside his eternal disdain for Kshatriyas for a while. For he trains Gangeya, the later Bhisma, and makes him an invincible warrior. This he learns to his own cost, because he goes up against his former pupil and has the mortification of not being able to best him, and even being in some danger of defeat before the gods intervene and stop this planet threatening combat. (He has a similar tiff with Ganesha too, and is credited with knocking off one of the tusks of that god, but the issue remained inconclusive in that instance also). His fighting Bhisma was actually something pretty remarkable, for he was fighting on behalf of a Kshatriya princess who felt she had some claim to becoming Bhisma's wife. Bhisma was like Parashurama, a lifelong celibate, and he flatly refused to imitate his guru's obedience. The important part of this story is that Parashurama could actually unbend enough to become a mentor to a hated Kshatriya and champion the cause of a girl from the same caste. The many long years he had lived had obviously softened him somewhat.

This defeat at the hands of Bhishma seems to have soured him once more, for he again refused to teach anybody but brahmins. Karna, one of the great heroes of the Mahabharatha, was of too low a Kshatriya caste to be taken notice of by Kshatriya martial arts masters. So he lied to the axe-man that he was an unfortunate brahman boy cursed with a talent for fighting and unable to get anybody to take him seriously. This lie must have gone to the soul of Parashurama, for he had been there. He immediately set about making the boy into a great warrior. Unfortunately for him, Karna had too much of his caste fortitude. Once, while his irascible guru was sleeping with his head on the boy's lap, a flesh-eating ant attacked Karna's thigh. His hands were not free as they were cradling the guru's head and rather than disturb the guru, he bore the pain. On waking up and seeing the blood, his guru instantly understood that the boy was a true Kshatriya, for only they could bear pain on behalf of others. Instead of admiring the boy for this fortitude and self-sacrifice, the angry avatar cursed him that he would lose his knowledge at the supreme crisis of his life and fall ignominiously in battle as a consequence. This was the authentic Parashurama note being sounded once again, relentless, furious and implacable in anger.

It has been theorized that the axe-man was perhaps a forest god who was gradually absorbed into Hinduism and given the status of an avatar of Vishnu. I doubt it. Forest gods are never so ferocious and perpetually in a bad mood. This is the Raudra Rasa incarnate, pure anger, the wrath of god in no uncertain terms. It has also been theorized that the story is an unconscious understanding of the process of evolution. The dwarfish human is succeeded by the brutal and hasty type before it is superceded by the more refined and elegant modern man. That is reasoning backwards and forcibly applying a theory to explain away what is uncomfortable to modern sensibilities. In any case, traditional Hindu theories of evolution speak of the devolution of man and his ages, not of his evolution, so Parashurama should be a modern, not an ancient type of god.

Whatever be the reasons, real and imagined, behind this fascinating aspect of the concept to avatars, there is no doubt that Parashurama is a real puzzle. It is perhaps in recognition of this perplexity that the ancient commentators called him both Khanda-parashu, he-who-strikes-with-an-axe as well as Nyaksha - the inferior (avatar). This incarnation is definitely a bit too strong for the average stomach and hence the respectful neglect he is held in.

No comments:

Post a Comment